Denée: carrière de ‘la bosse’

GUE-BE

Denée: carrière de ‘la bosse’

GUE-BE

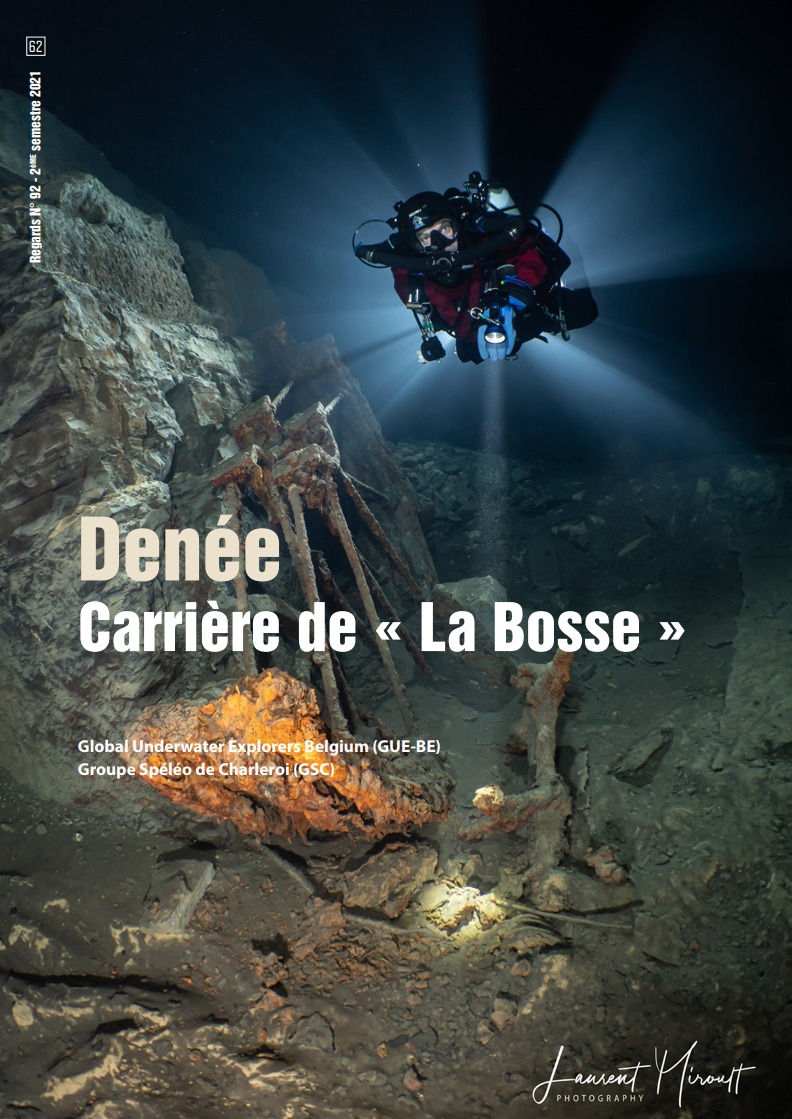

Ask the average Belgian cavediver whether (s)he knows the flooded mine of Denée and (s)he will likely confirm. This mine is managed by the Union Belge de Spéléologie (UBS). Most know it as a long defunct black marble mine. And yes, some old map circulates on the interwebs to help prepare for the dive. But that’s about it? Very little else is know about its history. And show a non-caver an underwater photo of the mine, and you’ll get a startled gaze and some mumbling of you being crazy going in there. Divers from Global Underwater Explorers Belgium (GUE-BE) and the Groupe Spéléo de Charleroi (GSC) jointly set up a project to better document the mine and make this piece of Walloon industrial archeology accessible to the general public. The project results are an accurate map and 3D computer model, a collection of stunning photographs by Laurent Miroult, and the discovery of a shaft that accesses a deeper section.

Preliminary results were presented at the 2021 ‘Cave & Wreck Night’ Conference, an annual gathering of GUE divers from all over the world.

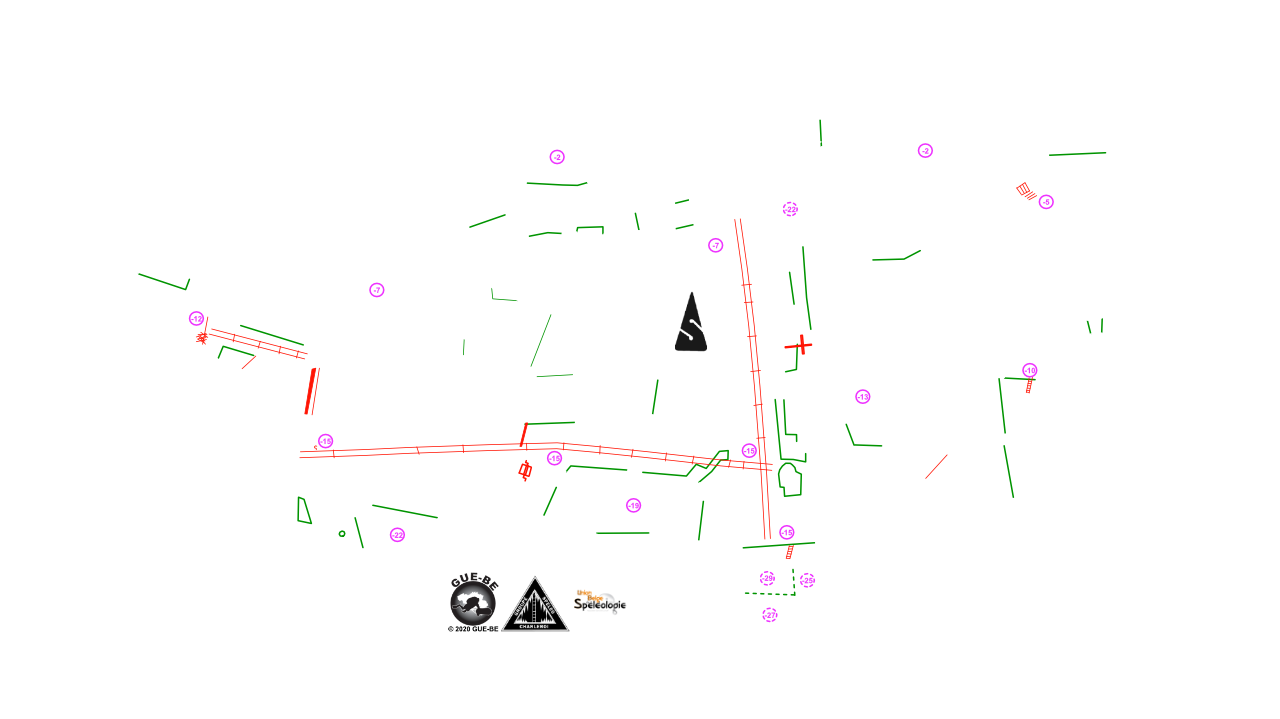

The map below shows the actual floorpan of the mine. It was derived from a detailed 3D scan of the entire mine. The red dots are clickable and pop up an underwater photograph at that spot. The colored areas are actual photographs of the mine floor where the rock was excavated. The blank dark areas are rock pillars that were left by the miners to support the ceiling and the hill above. Note the ring shaped features on the mine floor. These are car and truck tyres that were dumped in the mine after it was closed.

The idea of an underground project was born at the 2020 GUE-BE board meeting. After several successful projects in the Belgian North Sea, documenting the SS Kilmore and Westhinder wrecks, members voiced an interest in doing a Belgian underground project. The objectives were set and team members identified with the goal to document the ‘La Bosse’ flooded mine in Denée, update its old map, make a documentary and website with our research, photos, interviews, films and 3D material. The 16 team members brought their skills and interests, under the coordination of Blas Gallego Irles. As the most important team member, Olf Smetsers took care of the catering. Erik De Groef was responsible for video. Laurent Miroult was our secret photography weapon. Stéphane Riga connected with locals, authorities and historical archives. Johan Wouters took care of all things 3D and Ramon Camp set up this website. The Covid-19 measures limited the diver teams to 10. Dives were carried out in collaboration with the Groupe Spéléo de Charleroi (GSC) under the rules of the Union Belge de Spéléologie (UBS) that is responsible for the mine. The rules included, for instance, wearing a helmet which took a little getting used to.

We had some logo apparel made to promote the team spirit; a polo shirt, a hoodie, and because Covid-19 was in full swing, a mouthmask, all carrying the project logo and slogan “in tenebris omnia videmus” (literally “in the dark we see everything” or in free translation “we reveal what is unknown”).

The subterranean underwater environment is not particularly video friendly. There is no light and you can’t easily surface for some quick team instructions. You’d have to return all the way back to the mine entrance, wasting precious dive time.

A video team was put together with people that already produced underwater movies together in the North Sea and in fresh water. The video director defined in advance for each scene, what kind of shots were needed and under which lighting, and presented this in a hand sketched storyboard. After a couple of scouting dives, each video dive was then carefully planned at the surface, for camera configurations and light angles, staging of diver models, team safety, gas logistics, and avoiding unwanted interference with e.g. the 3D scanning team.

In terms of material, the team always used the same light-sensitive camera (Sony A7Sii) and the same video lights to maintain consistency between the shots. The video lights featured a wide beam angle and medium output (4000-8000lm) so as not to create hot spots or overexposed areas in the sometimes narrower passages. This benefited the continuity between images and avoids color adjustments in post-processing.

Johan planned to refine the old topo map through 3D photogrammetry. This is not the traditional survey technique based on azimuth-length-altitude. Photogrammetry is the art/science of creating 3D models based on overlapping 2D images. Each image is analyzed for key points. The key points of the different images are then compared and aligned. With triangulation, the location is calculated from which each image was taken, as well as the exact X, Y and Z coordinates of each key point. This is called a ‘point cloud’. The further workflow consists of manually cleaning up the point cloud where necessary. This thin point cloud is then detailed into a denser cloud, with just more points. Any 3 adjacent points are then connected by triangles (called “facet”) to create a "mesh". The mesh is a colorless model. To give it a more realistic look, the original photos are projected onto these facets. This creates a photorealistic 3D model. The concepts of photogrammetry date back to when man discovered perspective. But it was not until 1867 that Albrecht Meydenbauer coined the term photogrammetry. At the time, photogrammetry was a laborious manual process. With the current computing power, it is now possible to deploy this technology on a large scale. This is exactly what Google does to create the 3D ‘street view’ in Google Maps.

To scan the mine in all three dimensions, Johan use a scooter-mount setup with multiple GoPros and video lights mounted in a 360˚ ring perpendicular to the swimming direction. This allows simultaneously imaging the ceiling, side walls and floor. Scanning the entire Denée mine took three dive days. And then the real work started. Still images were extracted from the video and entered into the photogrammetry software (Agisoft’s Metashape). Due to computational and memory limitations, processing was done in multiple chunks. Then the different chunks were combined into a complete model. 51,000 images were used for the 3D Denée model, producing a point cloud of 40,000,000 points and a mesh with 12,000,000 faces.

In order to share the model on the web, we drastically reduced its size and detail. The ceiling was also removed to allow an easy “look inside”.

To experience how it is to dive inside the mine, take a virtual dive in the model below. Click inside the WebGL windows to activate the navigation and swim around. Use your keyboard to move forward (up arrow), backwards (down arrow), left (left arrow) and right (right arrow). Use your mouse to rotate left, right, up or down.

Once a detailed 3D model is available, it can be used to create derivative products. An example is an ‘orthomosaic’, which is a view where many photos are stitched together to create a very detailed image. By drawing out the contours of this top view and adding depth indications, a topographic map of the mine is created.

In search of historical and contextual documentation, we found very little Internet information on the specific site of the black marble quarry “Falige-Piette” of Denée also known as “La Bosse”.

However, the internet provided us with a wealth of scientific documents related to the geology of the Denée region as well as its history. The village was literally cut in half with two exploitable geological veins rubbing shoulders on its territory; the famous black marble (“Noir de Denée”) and small granite. At some point, the village knew more than thirty simultaneous exploitations. Thanks in particular to Father Dom Grégoire Fournier (paleontologist) and the relationship he had with the quarry workers, there are impressive black marble fossil collections preserved in the G. Fournier center of Maredsous Abbey and in the collection of the University of Liège. It should be noted that during the Middle Ages, it was iron ore rather than marble or granite that was predominantly extracted at the Denée village.

The notarized title deeds of the site revealed another problem: the extent of exploitation of the site identifies owners (3 different families), but this is not the case for the site as such. We therefore contacted the owners of the land adjacent to the quarry. Although they themselves had no or very little information about the exploitation period of the quarry, they welcomed us very kindly and put us in touch with two villagers who could help us. A third unfortunately died before we had a chance to interview him; he was the last worker to participate in the quarry exploitation in the village. Many e-mail and telephone exchanges preceded our interviews with the two villagers. The first we met was the late Bruno de Wouters de Bouchout, the last of 3 co-authors of a monograph on the history of the village. Unfortunately, Mr. de Wouters passed shortly after our first meeting. However, he gave us permission to reproduce the texts and images of his work in our publications. The second contact person is Éric Cobut. He is co-author of a book on the history of the village. It’s still in the works. Éric received us in a house built with local stones, where on the facade we can still read the inscription ‘marbrerie’ carved in the stone. We learned on this occasion that Éric’s great-grandfather was a marble worker and master polisher… Éric also explained us the origin of the name of the quarry “La Bosse”: the name comes from the slag heap of exploitation waste, which formed a mound in the shape of a hump. Rich in historical culture and anecdotes about the area, our interlocutor made us discover the village through his stories and explanations, but also through a beautiful walk. This guided walk, along the old exploitation sites of the Noir de Denée and small granite, opens the way to likely new explorations.

The Project Denée 2020 team in no specific order:

Olf Smetsers, Kim Eeckhout, Stéphane Riga, Blas Gallego Irles, Koenraad Van Schuylenbergh, Huub Martens, Johan Wouters, Ramon Camp, Laurent Miroult, Ben van Asselt, Roel Veugen, Bart Hoogeveen, Maxime Santermans, Erik De Groef, Jan van Winkel, Daniel Lefebvre, Pascale Somville

GUE-BE – Vereniging zonder winstoogmerk (vzw)

Zetel: Aarschotsestraat 55, 1800 Vilvoorde

Ondernemingsnummer: 0834 483 476

RPR: Rechtbank van Koophandel te Brussel, Britse Tweedelegerlaan 148 te 1190 Vorst

bestuur@gue-be.be

www.gue-be.be

Overview of press releases:

Regards v92